The Long Read: Aquabelle's history

The "Little Ships"

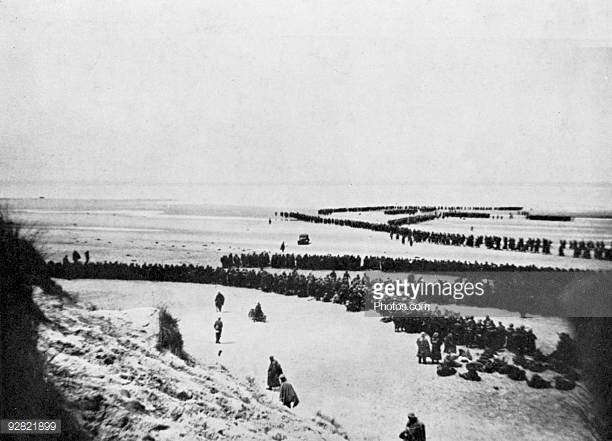

There are many reasons why Dunkirk Little Ships have a unique place in history. The image of these small private vessels saving British and French soldiers under German fire is powerful and was skillfully used by Churchill to convert an ignominious retreat into an example of British bravery, resolve and innovation. However, from the more distant viewpoint of the 21st Century, the most remarkable part of the Little Ships story is about their survival in significant numbers when almost all artifacts from those events 75 years ago have decayed and the soldiers they helped to save are fading away. So to board a Little Ship allows the visitor to make physical contact with a rare relic of the Dunkirk evacuation and to stand in the place where exhausted soldiers began to realise that they would live to fight another day.

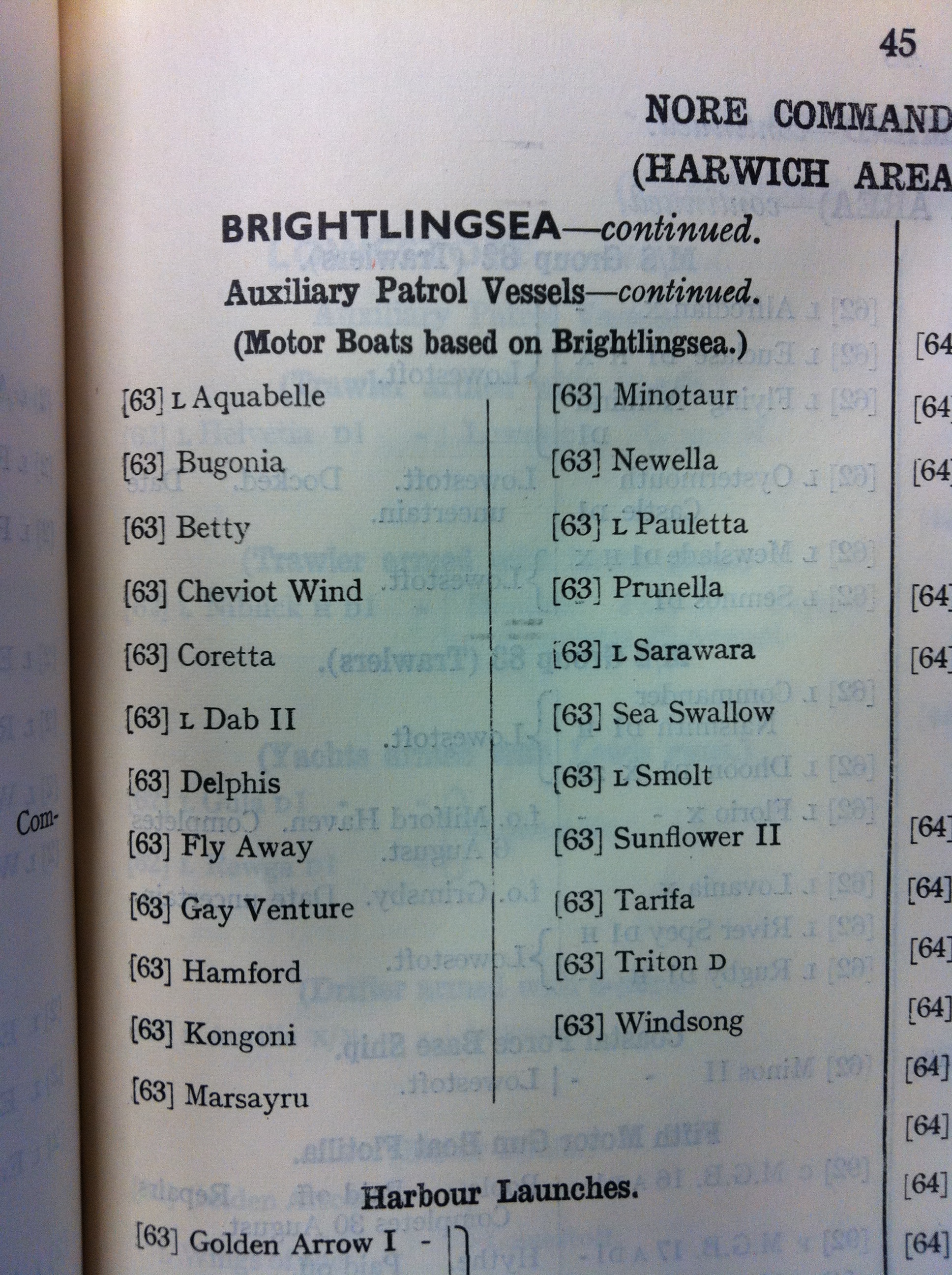

By surviving to the present day, the Little Ship must have avoided being sunk or irreversibly damaged during the Dunkirk operation, and also will have been maintained and nurtured through the intervening years against the ravages of rot and rust. Many have been lost to decay and neglect. The official records at the National Archives state that 464 "small craft" were used in Operation Dynamo and of those, 365 were recorded in June 1940 to have survived. This number has dwindled further over the years and it is difficult to estimate how many are still afloat and in a seaworthy state. The Association of Dunkirk Little Ships lists around 150 though many more are known to exist in the UK and abroad.

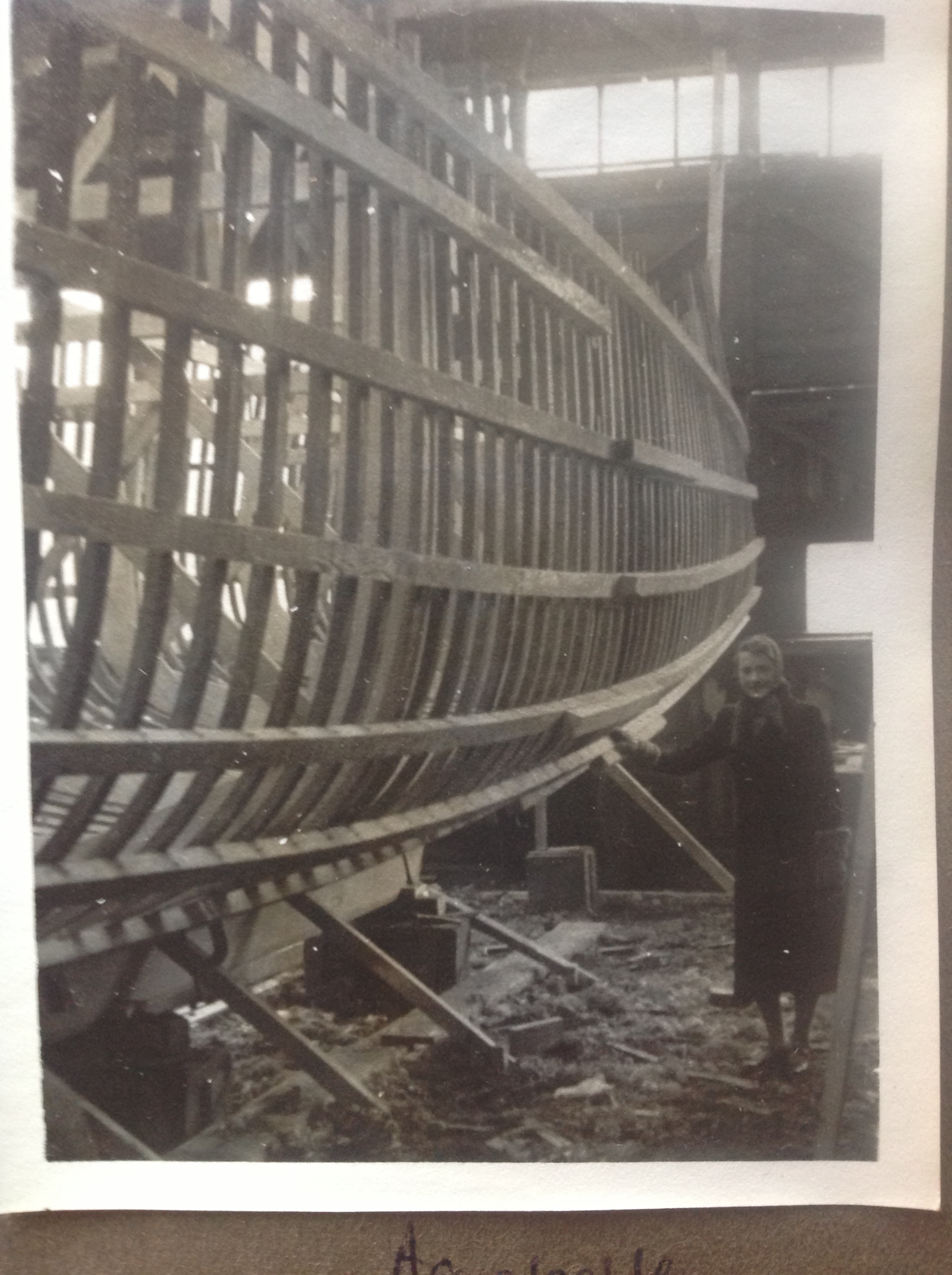

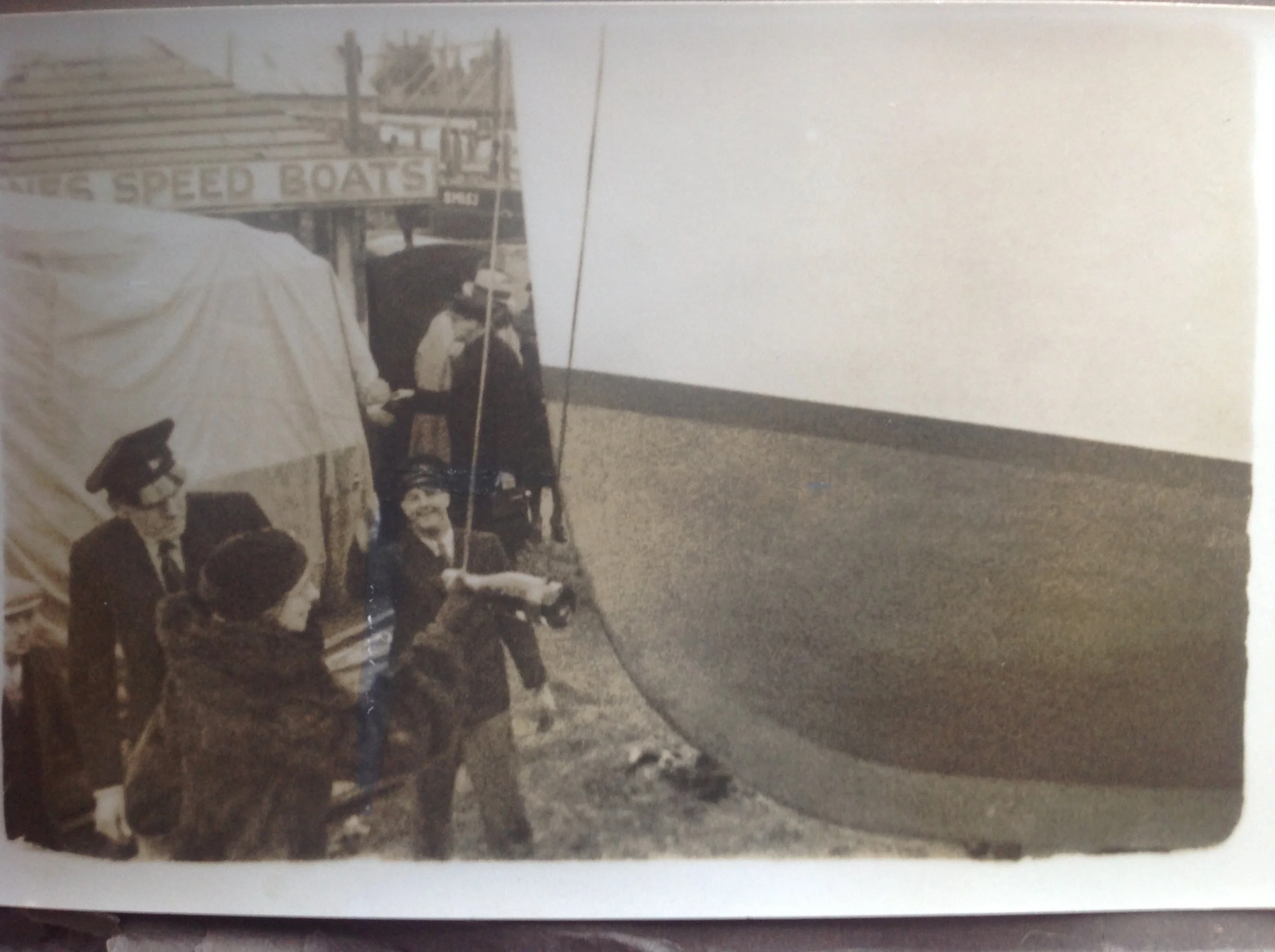

Aquabelle is one of these survivors. Her history before and after Dunkirk is unbroken, but not without incidents and accidents that could have led to her demise. After 75 years she is largely as she was built, and is now under ownership with direct family links to the man who commissioned her construction in 1939, Benjamin Taylor.